Depending on perspective, one can say that much of life is about meeting someone, perhaps one could even say meeting something. In most cases, those we meet are unfamiliar, although they may have some resemblance to someone we know. They remind us of someone else: a mother, a father, a sibling. Consider the metaphor of a ladder. Ada would say, “it’s good enough for Jacob and Wittgengstein, so it’s good enough for me.” We start out on the first rung, which may very well be our own dark self in the womb, then there is mother, and others.

Perhaps that is why meeting the Self again, in unexpected places, like the Alte Nationalgalerie in Berlin is such an uncanny experience. This was not a Hegelian confrontation with The Other, but rather meeting a coincidental self, a döppelganger who cast my notion of sovereignty, not to mention originality, right into the Spree. I was shaken enough that I repaired to a café I liked and thought about the work I had seen.

How much of this have I already seen and perhaps forgotten? I cycled through memory and then wondered if a mechanistic neurological description could perhaps explain the feeling I was having. I have no doubt that in the hands of a master, a neurological explanation could afford me some model of what happened to elicit the feelings of awe, of fear, and I could have wrapped it up neatly in the Savannah of Africa as a way of giving it a cause or an origin, but it had in no way offered any meaning whatsoever.

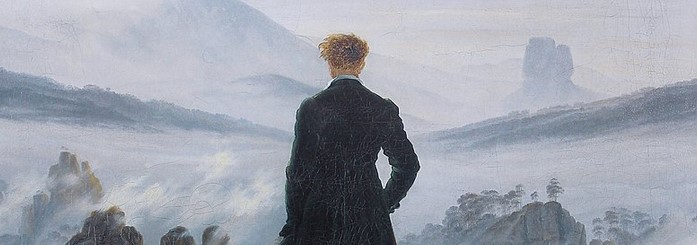

Many of us have seen the Der Wanderer über dem Nebelmeer. Arguably Caspar David Friedrich’s most famous painting, The Wanderer above a sea of fog resides in the Kunsthalle Hamburg, and ironically, I did not get a chance to see it when I went to Germany in 2018. The solitary Rückenfigur, or “back figure” looks out over a sublime rendering of nature. With a mood of careful contemplation, it has found a Romantic home in many people’s hearts, and yet, while I like and admire it, it’s not my favorite.

It was in the Alte Nationalgalerie on the Museumninsel in Berlin that I really first met Friedrich. My very good friend, confidante, and co-conspirator in the arts, Shannon Borg gave me explicit instructions to go see Monk by the Sea.

At this point, I won’t go into a biography of Germany’s greatest Romantic painter. (You can read that here) I am not an art historian nor a critic. Writing has always been the most important creative outlet for me, with visual artwork having laid in a torpor since first grade until I was in my early thirties, and even then it was a hobby that grew out of working on a website and publication materials for my job. Adobe Illustrator (with Photoshop as a finishing tool) finally allowed me some expressive freedom. I finally began doing illustrations to bolster my own work. I think it is a common path.

But this essay is not about that development. Let us get back to Friedrich.

For many years I had been quite enamored of Japanese woodcuts and Japanese art in general. This interest goes way back to my childhood and is worth a post of its own. Along the way in growing up, living and trying to capture some wisdom, the philosophy and literature of Late 18th and Early 19th Century Germany figured prominently. It began, as it did in history, with Kant and Goethe and grew from there.

So perhaps it was no wonder when I saw Friedrich’s work that I found elements of those interests seemingly blended in on top of one another.

Der Mönch bei Meer stands by its counterpoint, Abtei im Eichwald (Abbey in the Oakwood). The pictures elicit changing ideas every time I think of them or look at these old pictures from Germany. There are technical considerations such as the lack of a repoussir, or framing device that draws in the viewer’s gaze from a particular angle. It seems enough like a collection of horizontal gradient planes that art historians have considered it the first abstract painting.

The Abbey in the Oakwood is similarly composed of a gradient sky, dark near the bottom with those inscrutable oak trees reaching up. If you look at it upside down, they could almost be roots digging into the sky. The human figures are very small in both cases. They are not facing you and again, the effect of the Rückenfigur is not one of portraiture. You are there with the figure. The artist hopefully invites you to gaze at the landscape as well or “put yourself in the figure’s position.”

I think Shannon knew this, because I had already been using Ruckenfiguren heavily. My illustrated collection of microessays, Hyperborea is riddled with them, a stark tree in winter on a steppe somewhere out of the deep collective subconscious, or the contemplative tableau of Spring on Orcas Island.

Friedrich’s approach was a bit shocking in Europe at the time, but it makes all the sense when you consider it not as a work of 19th Century German Romanticism, but rather 19th Century Japanese woodcut.

In the hands of Hiroshige and Hokusai, humans occupy a similarly small place in a larger nature. This theme is not new to Japanese or Asian art, but they carried it forward in their particular media to a golden age. If you look at Hiroshige’s Chiyogaike Pond in Meguro, you can see this right away. The human figures are small and occupying only a small area near the bank. You can hardly notice them for the reflection of the trees in the water. In Hiroshige’s famous Plum Park in Kameido, (which inspired Van Gogh to copy it), the human figures are easily missed at first.

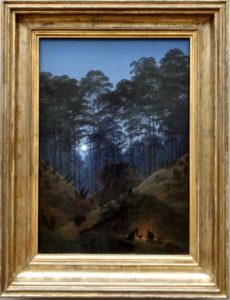

Sharing the gallery room with Monk by the Sea and Abbey in the Oakwood is Waldinneres bei Mondschein or Deep in the Moonlit Forest.

These moonlit trees and the small figures of humanity huddling by a fire speak to the sort of compositional placement I expect from a Japanese woodcut. Subconsciously, I think that’s what I thought it actually was out of the corner of my eye. It was only later, when I was in Dresden, walking by the Elbe at moonlight that I realized Friedrich had simply been painting from life. I looked up and there it was.

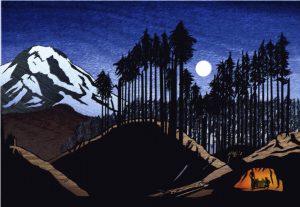

This picture inspired cover art I did for JW Capek’s second book in her Deerwhere Codex, Adrion’s Passage. The story is about an odyssey through the woods of a post-apocalyptic northwest, and so I couldn’t resist “filling in a bit more” a vision of as Friedrich may have seen it—placing the small human figures into a much larger and ancient landscape.

Dresden was the city where Friedrich worked for most of his life and unfortunately, my trip to Dresden only lasted a day. But I was able to go to the Albertinum and see, appropriately, Das Große Gehege, or The Large Enclosure.

I think my gaze considered it a photograph at first, but then I quickly recognized Friedrich’s handling of atmospherics and landscape composition. His color palette in this picture was already one I had been fond of and it shows up again and again in my work. I like to think of the Web banner of the home page of this site as being something Friedrich would approve of (and do far better) as Ada looks over the Puget Sound and the sublimity of Mt. Rainier.

Ada is fond of ‘getting lost’ in these moments of contemplation. The Nightingale’s Stone hinges on a moment of time when the contradictory concepts of mutability and permanency become meaningless, and in Berlin and Dresden, I met someone who had already been exploring these moments of transcendental consciousness.

For more of Caspar David Friedrich’s work and brief biography

Ada’s take on Friedrich can be found in the September issue of the 2020 Trinity Anthology from Blue Forge Press. (Amazon link)